In February 2018, construction crews building a new school here uncovered a long-forgotten cemetery containing 95 graves.

The majority of the remains are thought to belong to Black convicts who labored and died here more than 100 years ago. Private sugar farmers leased these men from the state penitentiary and profited from their labor between 1875 and 1910.

Despite the discovery, the Fort Bend Independent School District forged ahead with construction. The building design was altered to allow the remains to be reinterred where they were found. And today, students steam past the cemetery on their way to autoshop and culinary classes.

But the revelation that Sugar Land was once home to the largest convict lease plantations in the state has forced residents to take a closer look at the land on which they live, play and work.

This land holds the key to understanding how we got here and how we can begin to heal.

Long before Sugar Land became the “sweet” city it is today, this land was stewarded by the Karankawa and Tonkawa people.

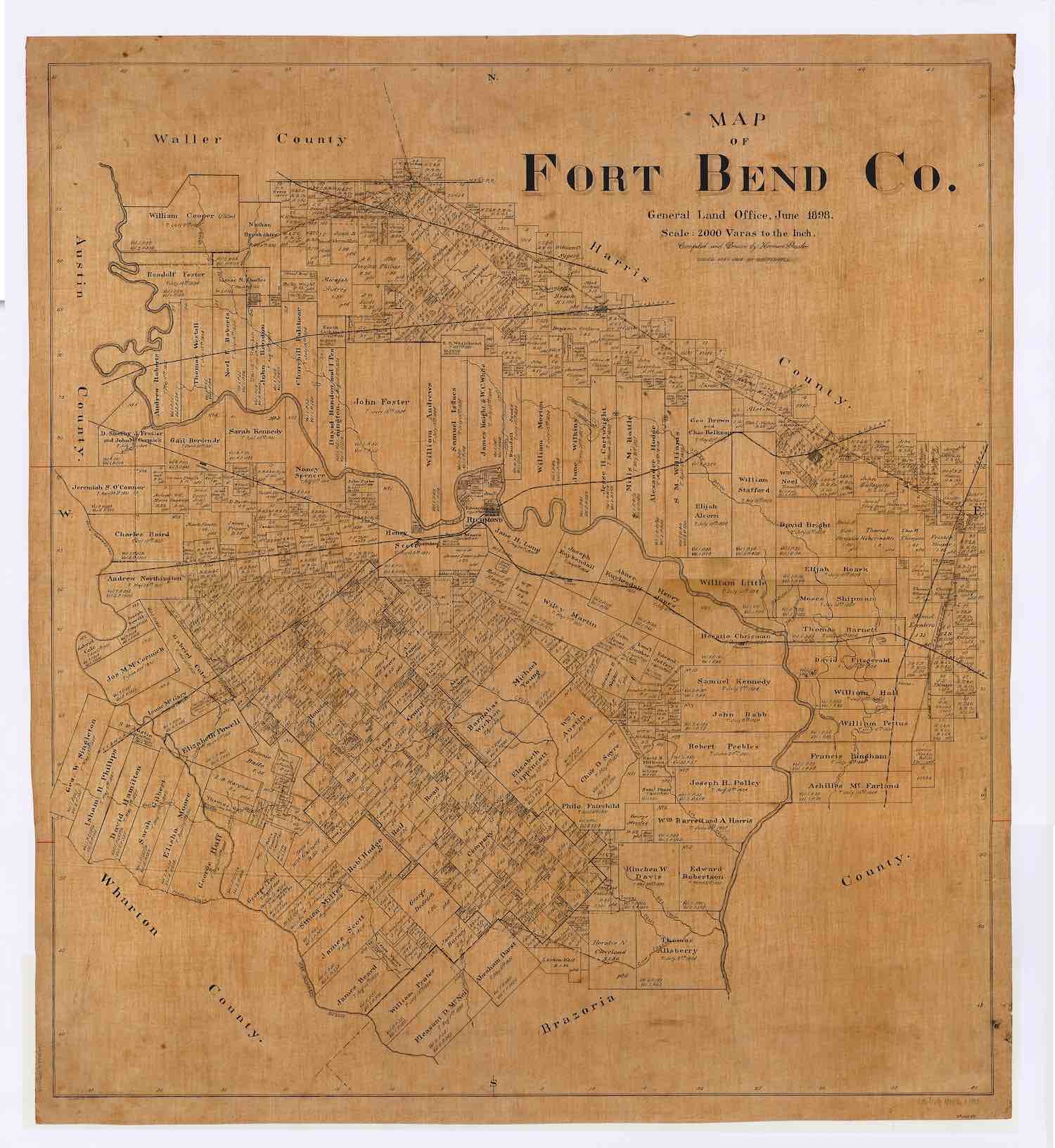

These and other Native American tribes were forcibly displaced in the 1820s when the Mexican government permitted Stephen F. Austin to colonize Mexican-Texas. Austin issued around 300 land grants in which each family received a league equal to 4,428 acres under the condition they farm and improve it.

The land in and around modern-day Sugar Land was some of the most desirable real estate in Texas.

Austin’s colonizers brought slaves to the area, and built up large plantations where they harvested cotton and sugarcane.

These were the largest slave plantations operating in the area in 1860, just before the Civil War began. Enslaved people made up over 30 percent of the total population of Texas at the time.

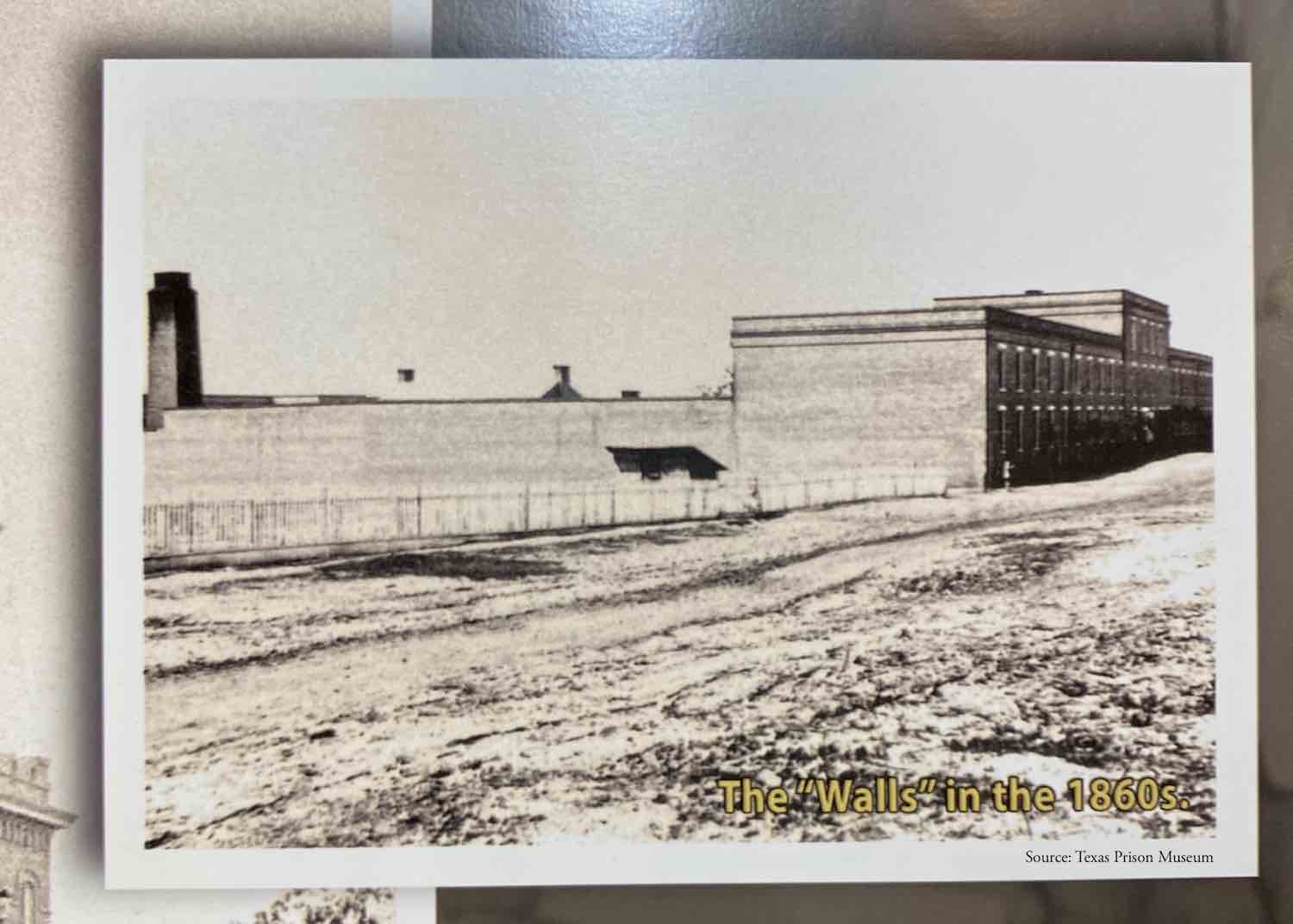

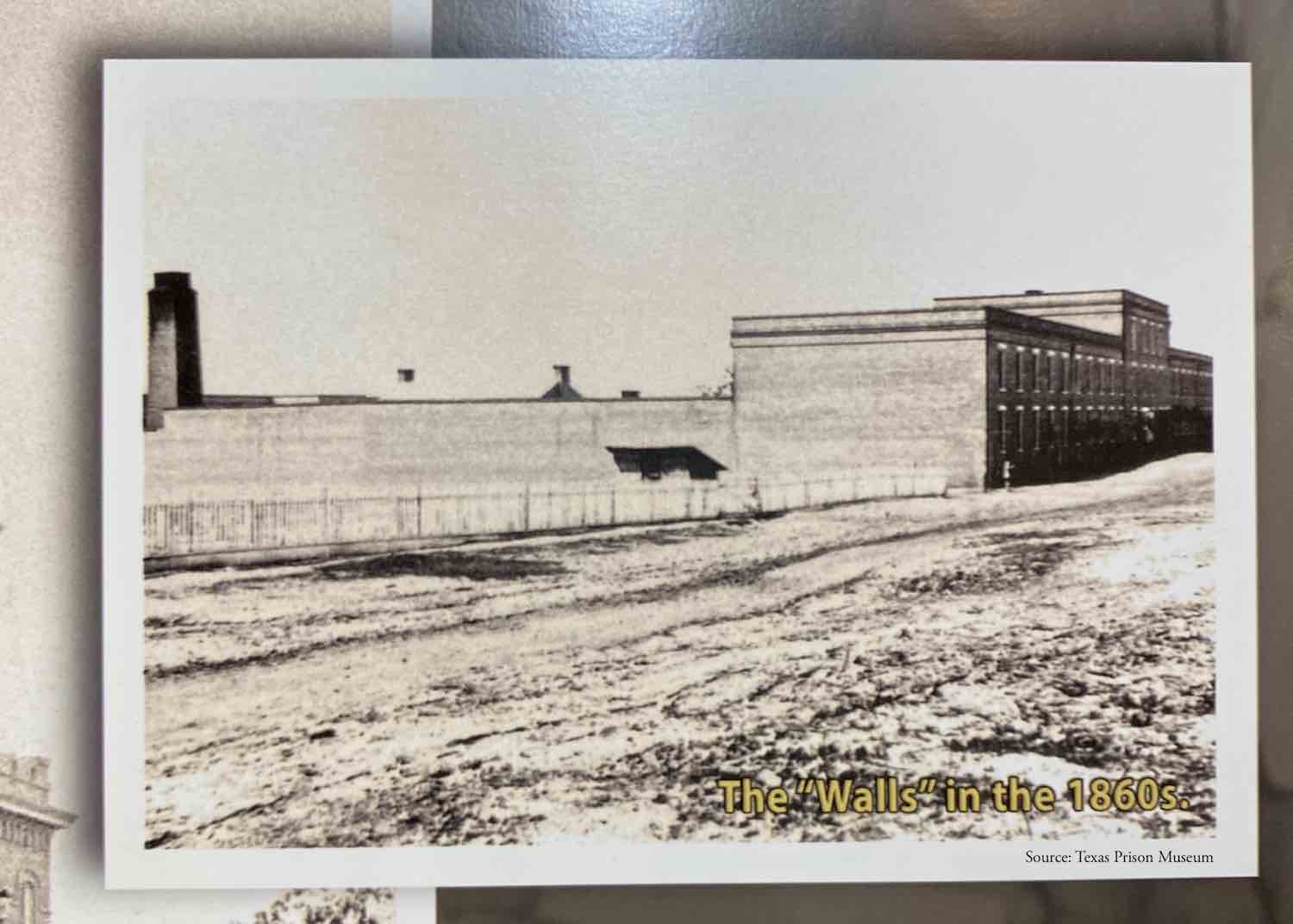

Texas’ prison population grew slowly until the Civil War came to an end. From 1860-1865, the prison admitted, on average, 43 new inmates per year. In 1866, it admitted 261 new inmates, and 75 percent of them were Black.

The state didn’t have space in the penitentiary to house all the new prisoners, or the money necessary to feed and care for them. So, they began leasing convicts to railroad companies. The railroads agreed to feed and house the inmates in exchange for their labor.

By 1875, convicts were being leased out to work on private sugar and cotton farms, as well. In Sugar Land, these three former slave plantations were utilizing convict labor.

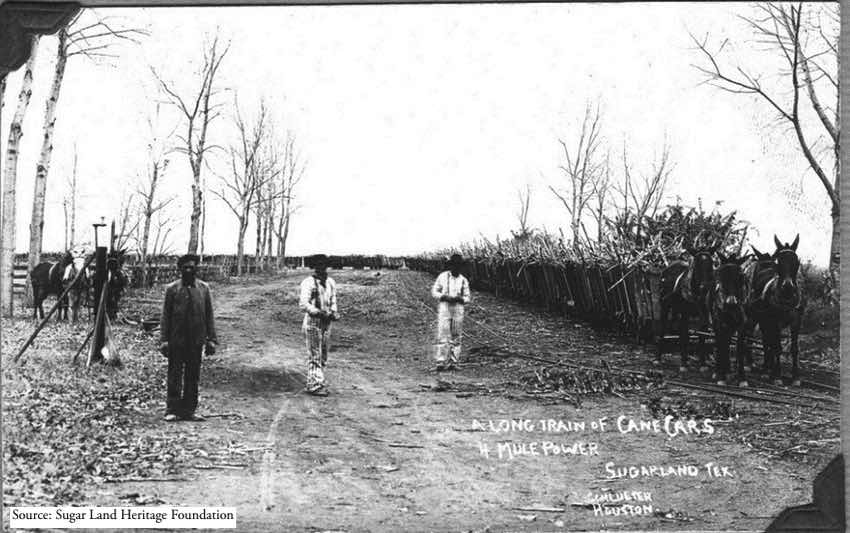

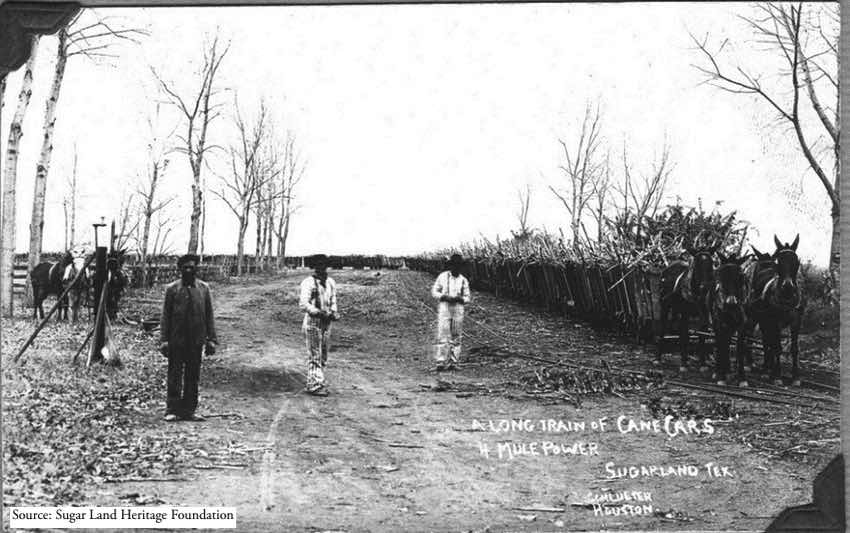

Black men made up the majority of convict laborers put to work on sugar farms.

The area’s sugar growers were seeing so much success using convict labor that outsiders began to take notice. Two businessmen bought the former slave plantations in modern-day Sugar Land. And, over the next three decades, they operated the state’s two largest convict lease plantations side by side.

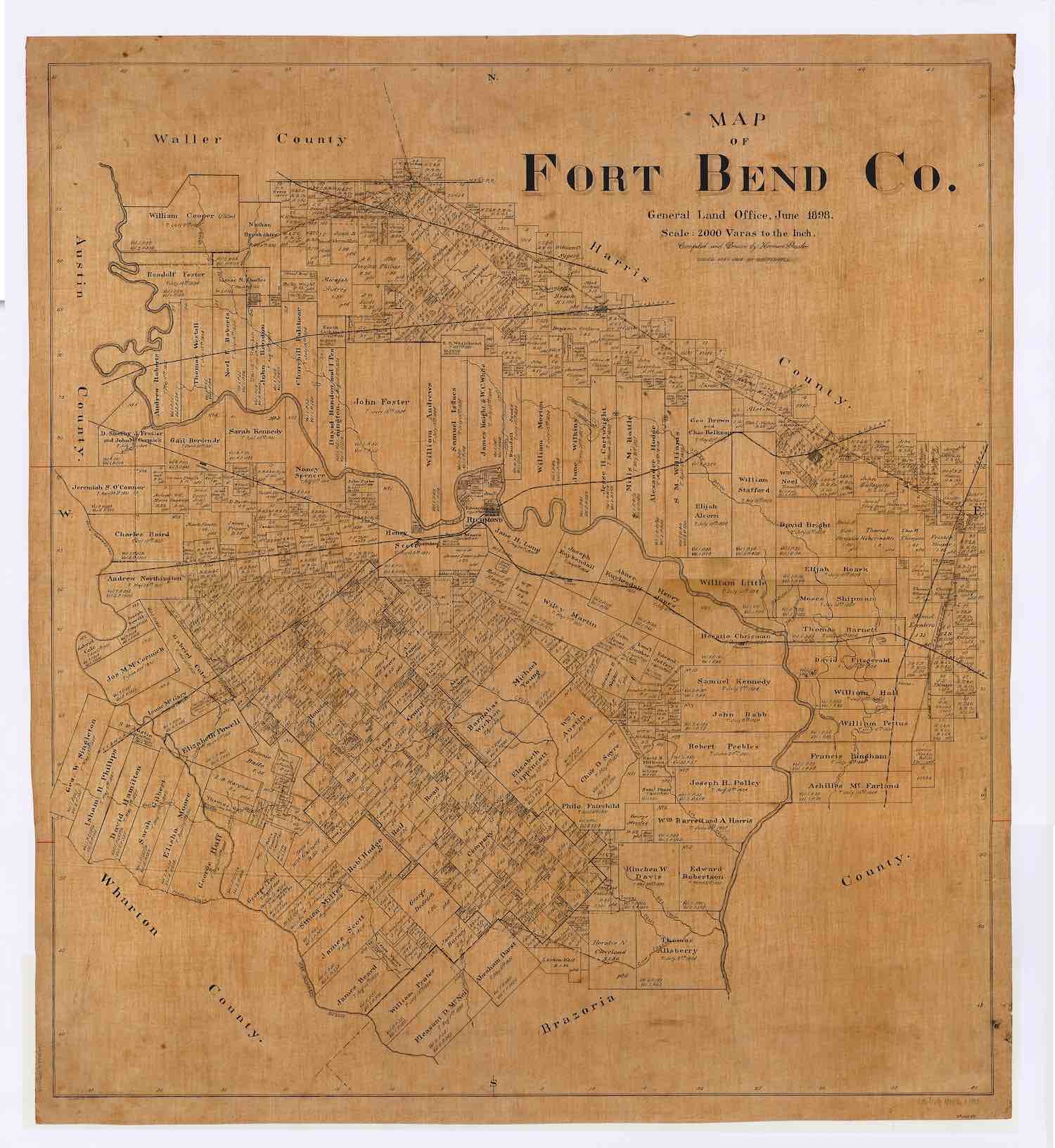

The cemetery discovered in 2018 was found on the former convict lease plantation owned by Littleberry Ambrose Ellis. In the 1880s and 90s, Ellis purchased over 5,000 acres of land in modern-day Sugar Land and leased, on average, 150 convicts at a time to plant and harvest sugar cane.

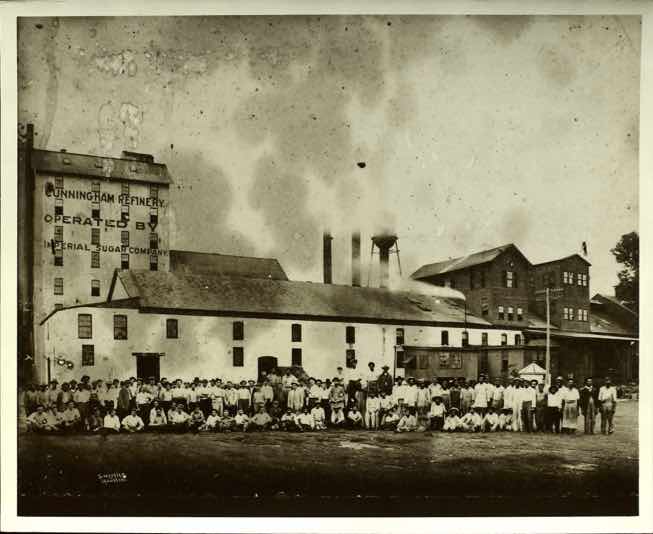

The plantation next door was owned by Edward H. Cunningham. He eventually owned over 12,000 acres of land and relied on convict labor to fuel his sugar empire.

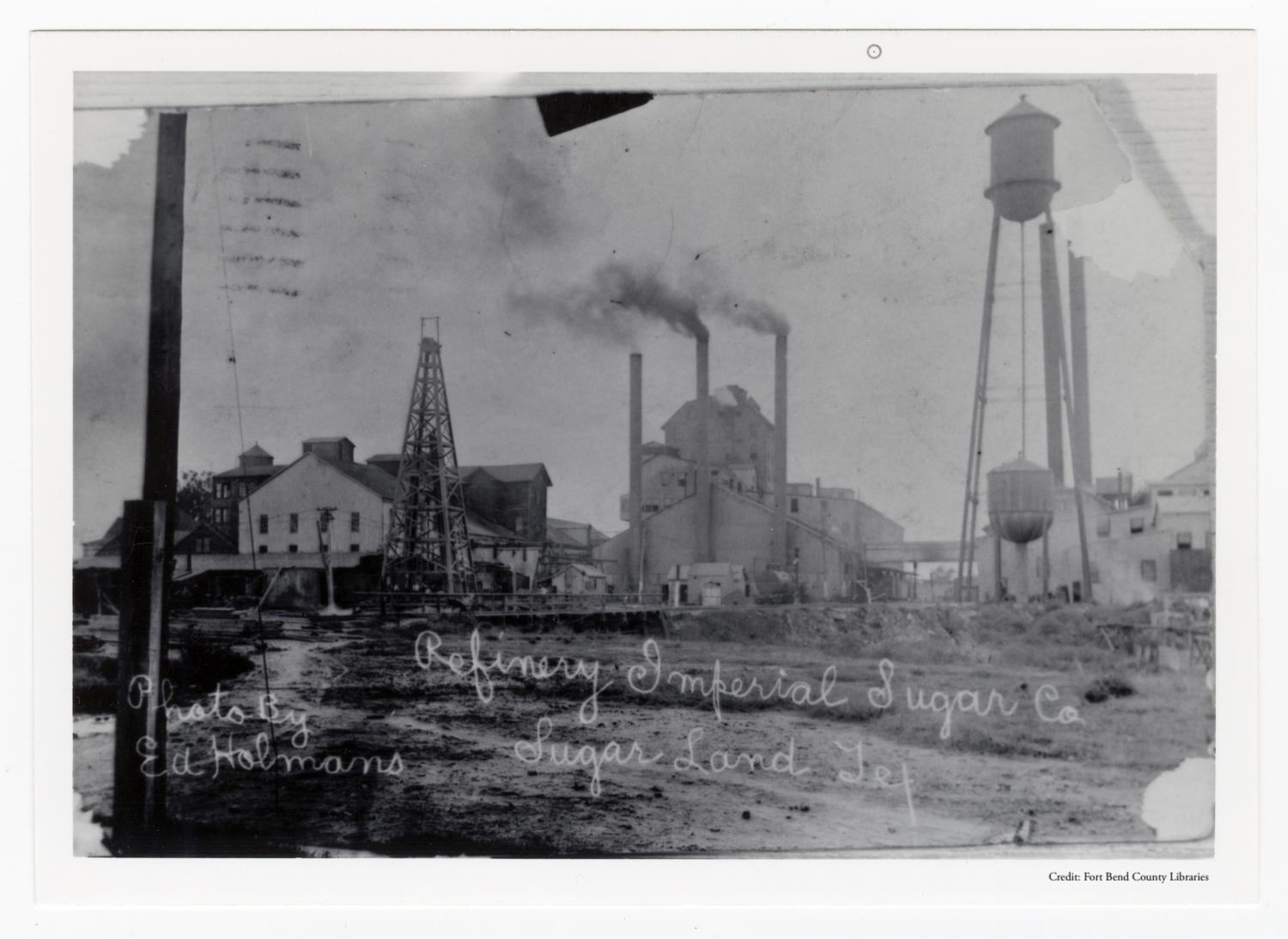

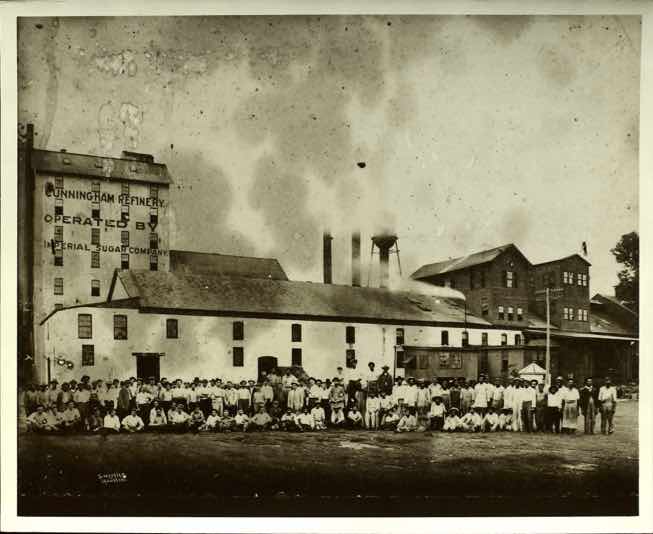

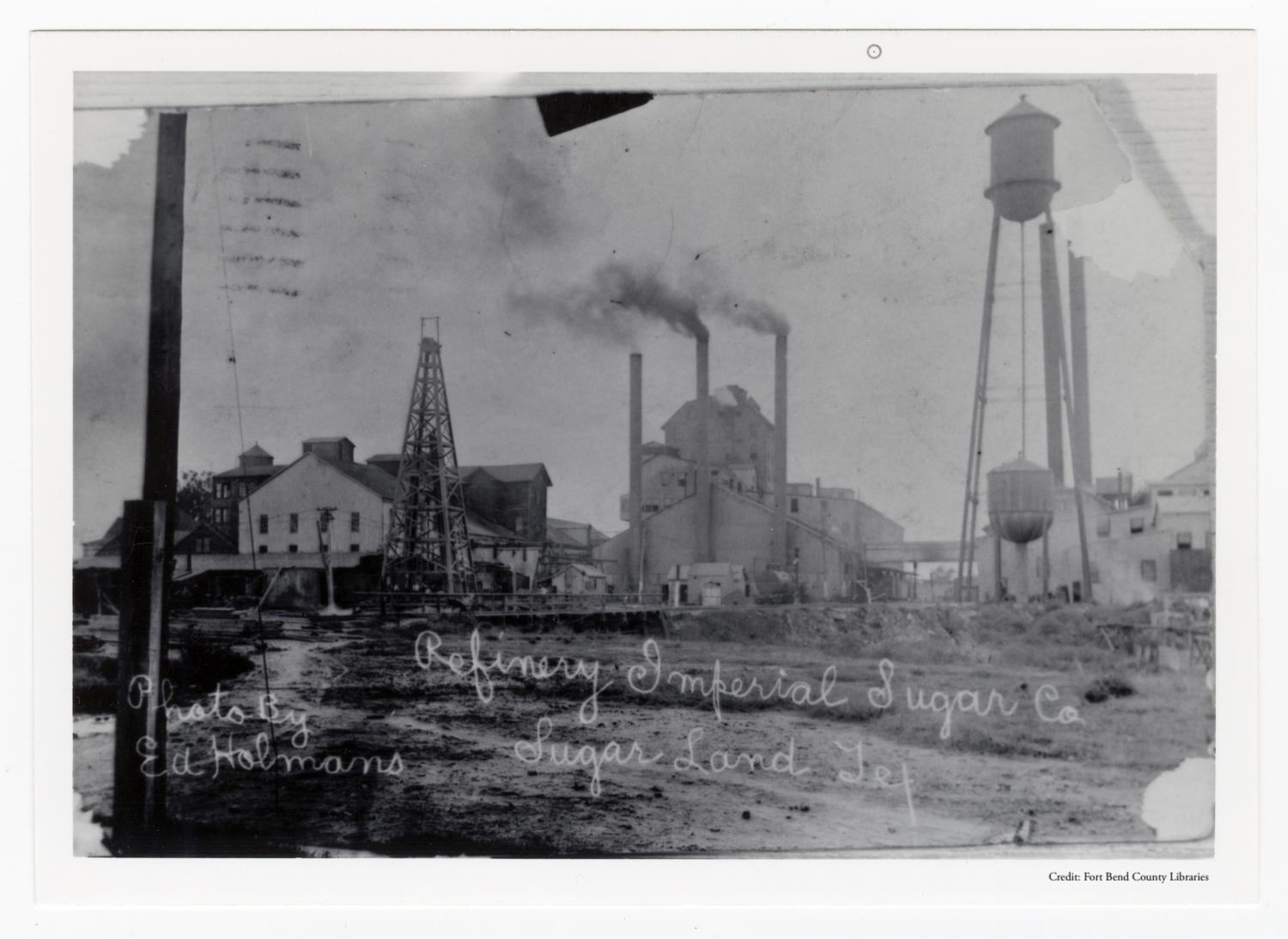

Cunningham’s plantation went into receivership in the early 1900s and was taken over by I.H. Kempner and William Eldridge, who created the Imperial Sugar Company there.

In November 1907, following the deaths of L.A. Ellis and his sons, the Ellis plantation also went into receivership. His widow sold it to the Imperial Sugar Company, and just three months later, the land was sold again–this time to the State of Texas.

Texas began operating its own prison farm on Ellis’ former plantation. At first, it was called the Imperial State Farm, and later, Central State Farm. As part of the sale, the prison was contractually obligated to sell the sugar cane convicts harvested there to the Imperial Sugar Company, a practice that continued even after convict leasing came to an end in Texas.

By the early 1910s, Sugar Land had become a company town. Residents either worked at the Imperial Sugar Company or for Sugarland Industries, which operated all the local stores, hospitals and businesses. The price of their healthcare, food and clothes was all deducted from their paychecks.

In 1958, the company town of Sugar Land incorporated and became the City of Sugar Land. In the decades that followed, industrial complexes and master-planned communities spread across the landscape.

In 2003, the land containing the remains we’ve come to know as the “Sugar Land 95” was sold to a developer to build a new residential housing community called Telfair. At the time, the location of the cemetery was still unknown.

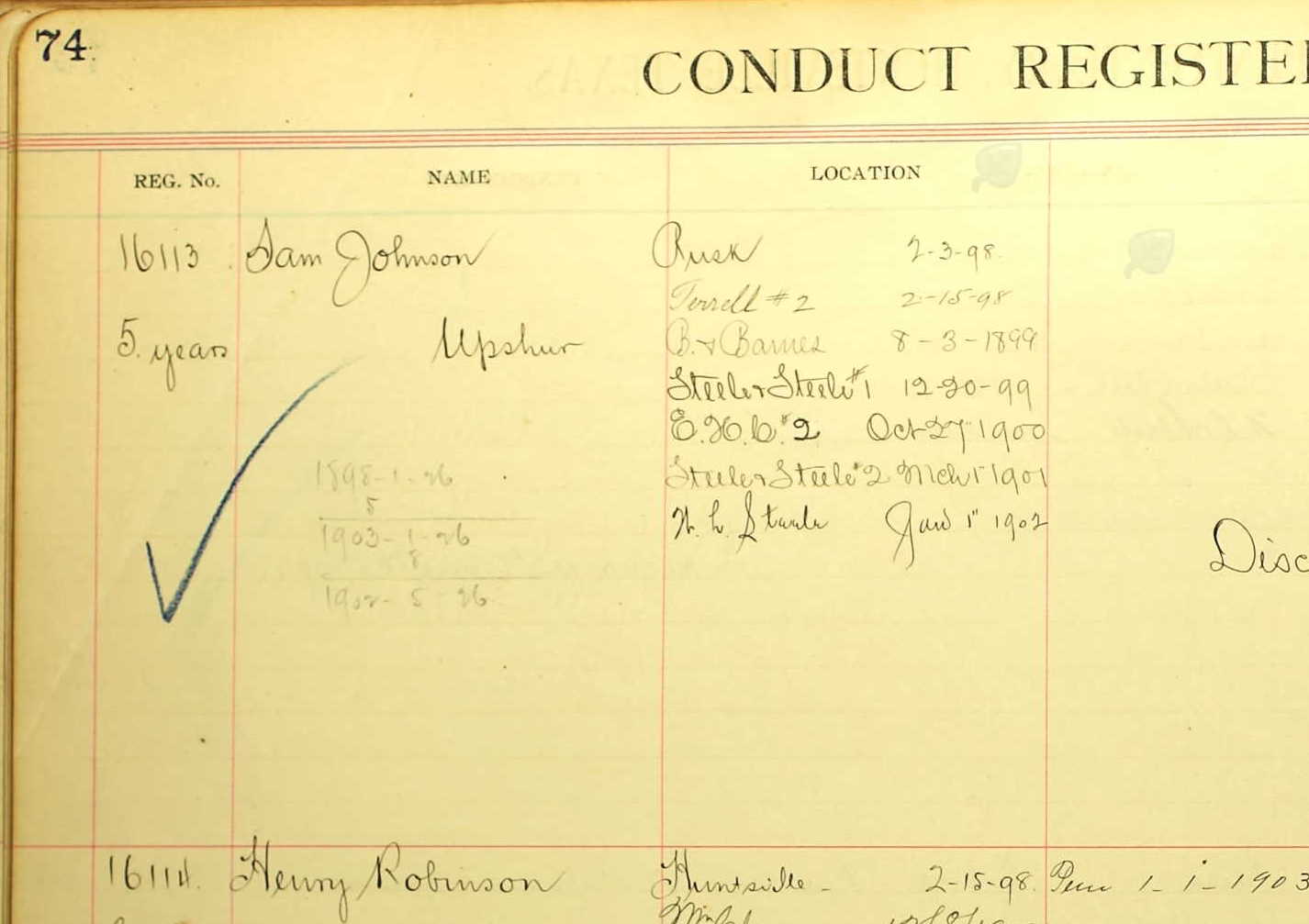

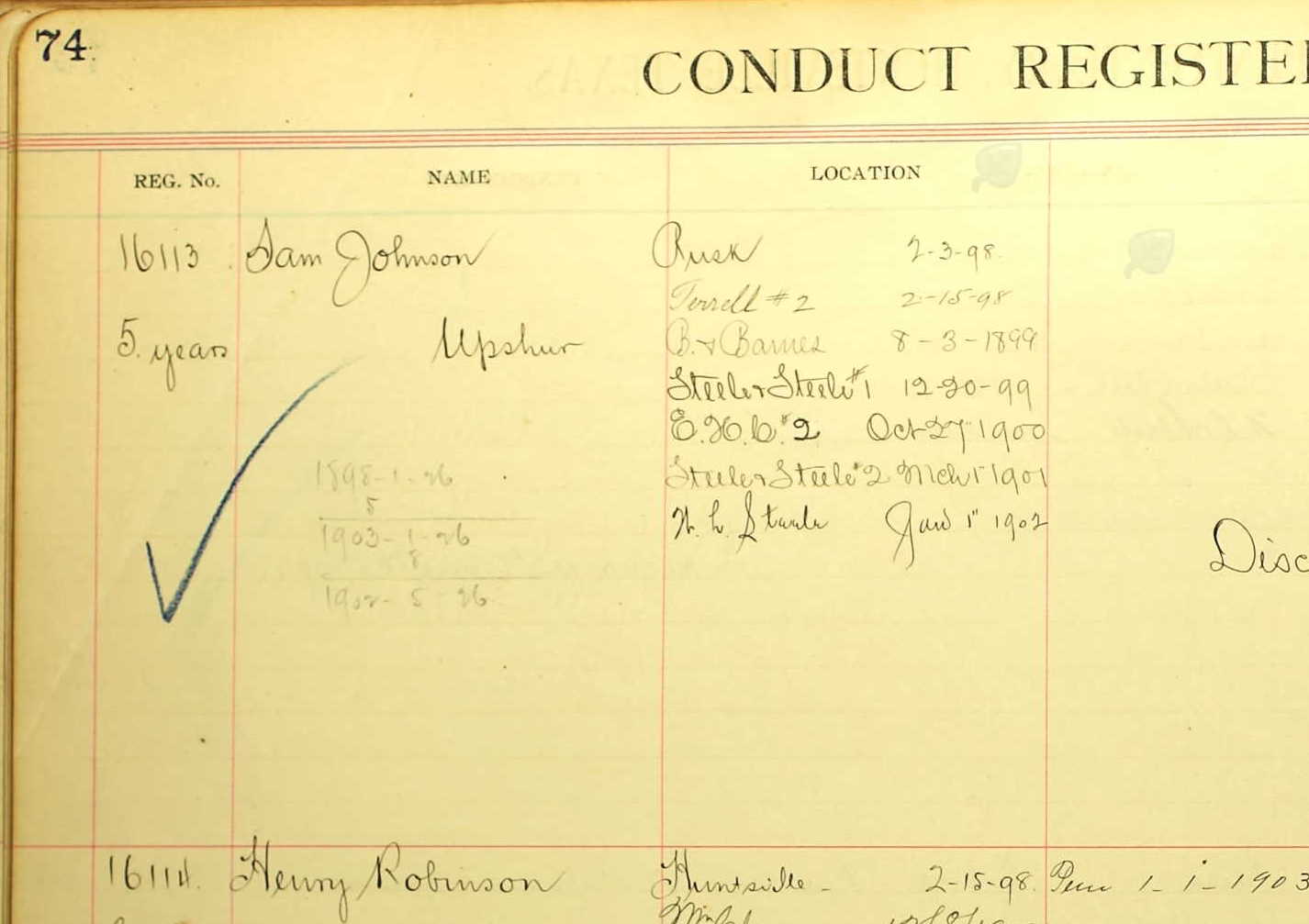

In 2011, Fort Bend ISD purchased 65 acres in Telfair from the developer. And six years later, construction on the James Reese Career and Technical Center began. We used old prison records to determine who might be buried in the cemetery, and we’ve slowly begun unearthing their stories.

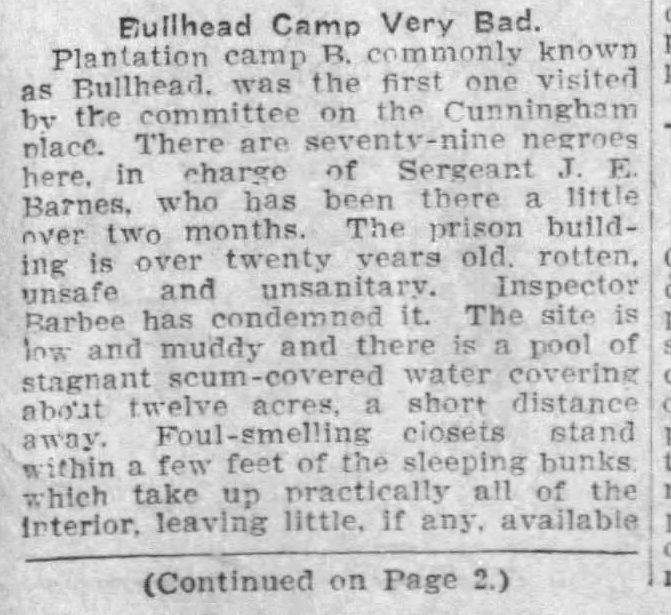

In late 2020, two and a half years after the cemetery was discovered, Fort Bend ISD and its archaeologists published a report detailing all the research they’d done on the cemetery. In it, they announced the cemetery’s official, recorded name: The Bullhead Camp Cemetery.

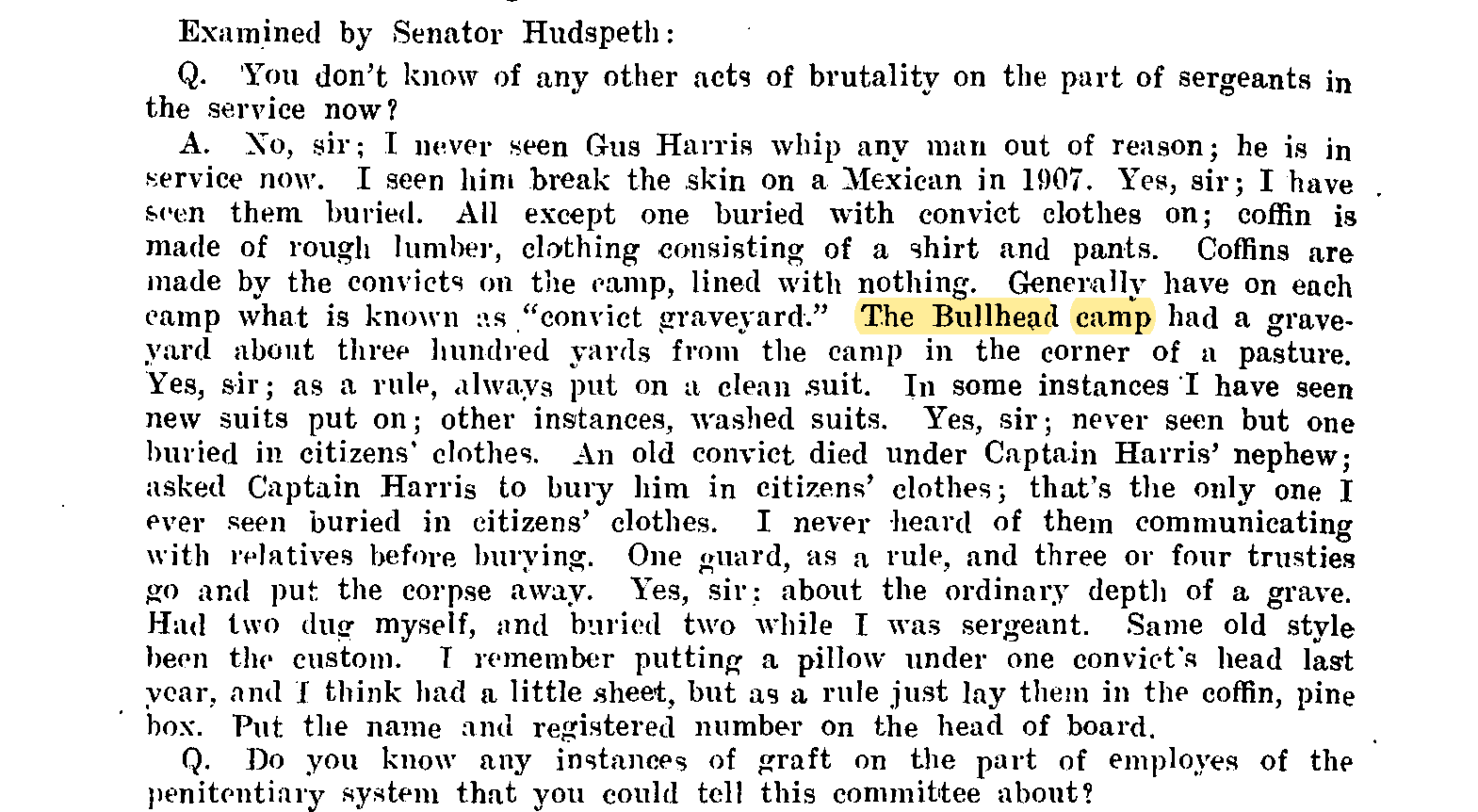

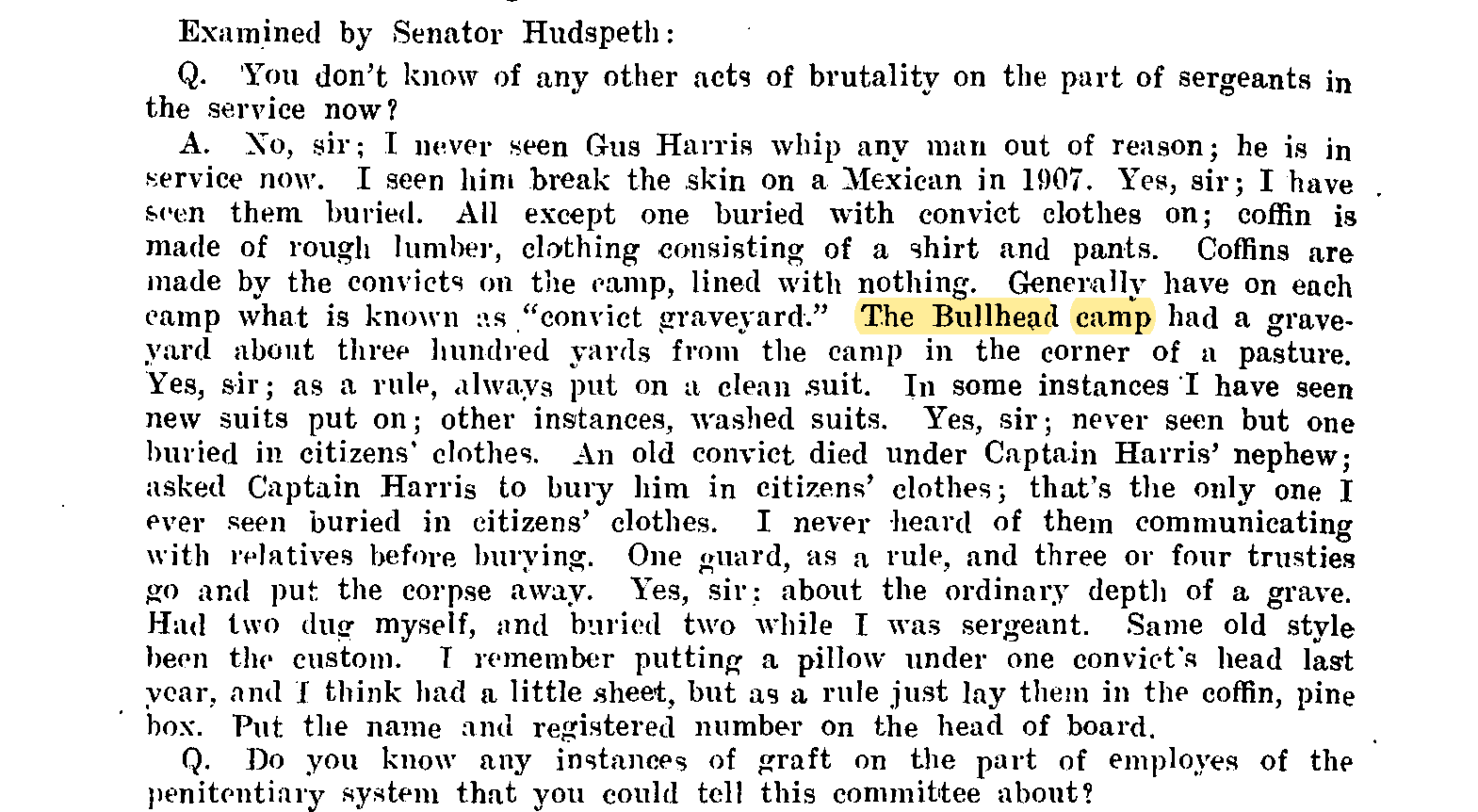

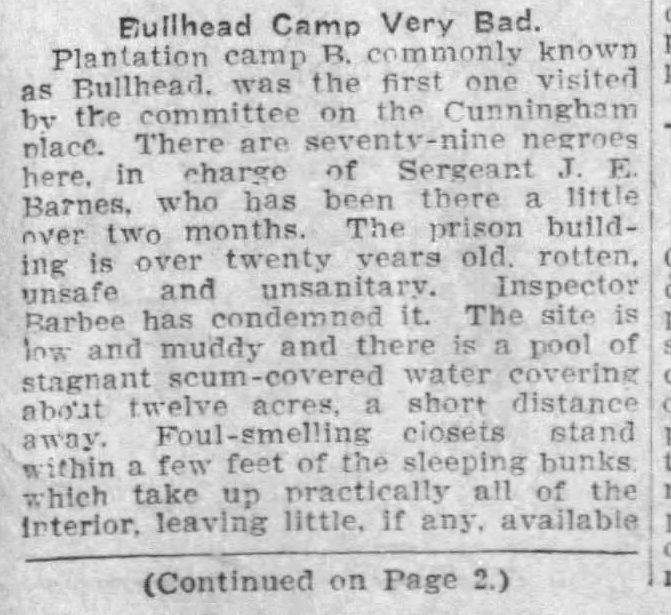

The researchers came across a reference to a cemetery on the “Bullhead Camp” in an investigation into the prison system conducted in 1909. That’s the name on the cemetery signs today, and it’s the name that will appear on the official state historical marker soon to be erected on this site.

But further investigation revealed that the cemetery containing the Sugar Land 95 is NOT the Bullhead Camp Cemetery. The cemetery mentioned several times throughout the 1909 report and in news articles a decade earlier was actually a camp on Cunningham’s plantation.

And, as you can see, the cemetery containing the Sugar Land 95 was on Ellis’ land.

That means not only is the Sugar Land 95 cemetery misnamed, but the real Bullhead Camp Cemetery is still out there somewhere.

We don’t know where in this large area it is, but it’s likely been built over at this point. There’s not much land left that hasn’t been developed.

We owe it to the men buried there–and their descendants–to look for it and to correct the record. They have stories worth hearing, and their existence shouldn’t be erased.